https://nadaesgratis.es/admin/hablemos-claro-de-y-como-dani-rodrik

Text: Jordi Paniagua

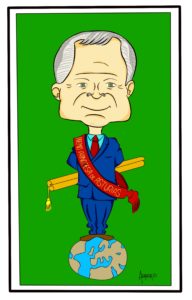

Picture: Carlos Sánchez Aranda

Dani Rodrik points out in a brief autobiographical note that he has earned a heterodox title thanks to his application of the most orthodox methods in economics, which have led him to be one of the most respected economists by profession and recent Princess of Asturias award. Of Sephardic origin, he would have been Havard’s Professor Daniel Rodríguez in a kinder version of our history. But his family ended up in a more tolerant Constantinople than Erdogan's Turkey, as he remembers and denounces here o here. Rodrik speaks straight and called the events of 2014 a coup d'etat here.

To the purest spirit of Ortega-y-Gaset he has understood that the university's mission extends beyond the university halls and has jumped the classroom barrier in three directions. The first with a political commitment against the authoritarian drift of democracies and has promoted the Economics for Inclusive Prosperity network to promote inclusive growth policies.

The second is the dissemination of his research that has circled the political economy of globalization, studying aspects such as economic growth, international trade, and the role that democracy plays. He has the ability to make himself understood clearly in blogs, press, and especially in books that are pleasant to read as well as profound. His most recent book, which has the Wildian virtue of difficult translation into other languages, could be understood as let’s have an honest debate on trade, which summarizes his thinking about the economic profession, economic science, globalization, democracy. He cautions the reader of his previous books, Has Globalization Gone Too Far?, The Globalization ParadoxandEconomics Rules, that they will not learn much new. However, with Rodrik one always ends up learning something, since he has the virtue of speaking clearly.

In this last book, we are introduced to a Pirelli democracy. Democracy is nothing without control (that is, without respect for the law). It is another form of tyranny: that of the majority perverted by lexicon (“democracy”, “freedom”) and forms (voting and ballot boxes) that hide their authoritarian nature. Similarly, globalization is nothing without control. Ultimately, this is the central argument of his critique of globalization in his well-known globalization trilemma: that national sovereignty, globalization, and democracy are mutually exclusive. Two elements of the sovereignty-globalization-democracy triad can be pursued simultaneously, but always to the detriment of one of them. If a nation increases its national sovereignty, it has to choose between the advantages of trade or democracy. Rodrik argues that globalization has gone too far and has renounced democratic controls.

At this point, I must note my bias. Part of my doctoral thesis consisted of an attempt to find empirical evidence on Rodrik's trilemma. I exchanged correspondence with him and I have a photograph hanging with him in my personal “hall of fame" with Deaton or Phelps, so it may be difficult for me to be objective. However, unlike the impossible trinity of an open economy (the ability to achieve only two of the three political objectives: financial integration, exchange rate stability, and monetary autonomy), Rodrik's trilemma is as true as it is general (for example, what exactly does thin globalization really mean?). Empirical evidence has so far been elusive. Partly because it is difficult to identify the unique effects of globalization. According to Autor et al, many of the jobs that international trade has supposedly destroyed are early victims of technological progress (see here and here). Therefore, we can interpret it as a conceptual or discursive framework, but hardly as a structural economic model.

For one example, one of his most poignant criticisms about the misgovernment of globalization is the dispute resolution system through international arbitration tribunals here. Their main argument is that only foreign investors can use this dispute resolution mechanism. It is something that we know well in Spain, where we stake € 10 billion in arbitration awards and the loss may be greater if we take into account the effect on foreign investment as highlighted here. However, this is one of the main arguments that purple and green populisms use to oppose further economic integration, ignoring the advantages of this system for FDI or trade. It is one of the reasons, among others, why Rodrik warns in his latest paper that globalization feeds populism (in the style of Agent Orange by A. Rose).

At the risk of his ideas being kidnapped by populists, Rodrik has followed through with his criticism of globalization, but unlike the homeopathic economists who pick only his sweetest cherries, also highlighting its advantages. Rodrik is the most orthodox economist among heterodox economists; he bluntly defends income tax, pensions, bank deposit insurance, labor requirements for beneficiaries of social assistance, conditional transfers, independence a form the central bank, and trade in pollution quotas. He even assures, that the concept of the most favored nation, the flagship of globalization, is one of the best economic policies that have changed (for the better) the economic structure of countries. He exposes here and here that the marginal benefit of trade liberalization is lower than that of the international labor market and proposes a temporary migration regime between countries.

Since Ricardo, however, we know that the advantages of trade list a positive computation for the winners and a negative one for the losers. In net terms, the positive gains are so great that they could compensate the losers and all win. Rodrik makes the point that the losers are rarely compensated (for example, the sectors with the most import competition) and that economists have not had an honest debate about it. Fearing that complex reasoning is not understood or misinterpreted, he argues that populist sores arise from both biting the tongue on both sides of the Atlantic.

This undisguised criticism that Rodrik makes of fellow economists (pointing directly to his responsibility for Trump's coming to power) is the third barrier that Rodrik has broken: the epistemology of economic science and economists. Just a few days ago, in a series of tweets, he reflected on the profession of academic economics and its problems in including minorities. It describes three characteristics of the academic economy: class, hierarchical, and full of jerks, with a high tolerance for little respectful behaviors. Dani Rodrik confesses that at the beginning of his university career he hesitated between specializing in economics or sociology. When sociologists analyze our field, they tend to coincide with Rodrik's vision: according to this study, economics is the field that presents the highest index of persistence in the hierarchy and consensus on collective norms. This is partly explained by our particular editorial process (here and here).

In his book Economics Rules (another title with a double meaning that could be translated as the rules of economics but also as that economics is cool) summarize his vision of economic science and economists (read both the review in NeG and the book). He made me rediscover Borges and I usually start my classes with the 20 commandments (10 for economists and 10 for non-economists). He argues that economics is a particular form of social science and that precisely what makes it a science are its models. But he warns that the economy is more diverse than some would like and from what others grant. Let's have honest discussions: let's admit more diversity in our field, our colleagues, and our models and ideas. We could start by speaking straight, as Dani Rodrik does.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario